Feature Artist Spotlight: Lucas Rueckner in Berlin's Creative City

Two and a half years ago, artist Lucas Rueckner left Peru to search for his ideal creative haven. Berlin’s creative city is rough and riddled with distractions whilst his work exists in the blissful space between his memories, imagination and reality. How does he transform the indefinite cultural impulses into focused artistic production?

I propose that the answer lies not in an artist’s guide on how to cope in a city filled with creatures of leisure and free spirits, but in each individual’s definition of ‘creativity’ itself. To Lucas Rueckner, it is honesty and passion combined. He treats it as an object of analysis that is independent of his knowledge or identification with it: what do the movements and colours in his work tell him about how he feels and where he is? And what about during a global pandemic, cultural standby and surge of ‘fake news?’

This is a testimony of the considerable distances he has traveled physically and emotionally. We see you, Lucas Rueckner, for the raw quality of your intentions and doings:

“If you are experimenting in a new city, you can loose yourself into so many directions. There are too many distractions from what you really want to do here. Since the beginning, I wanted to do a Master in Art Therapy.”

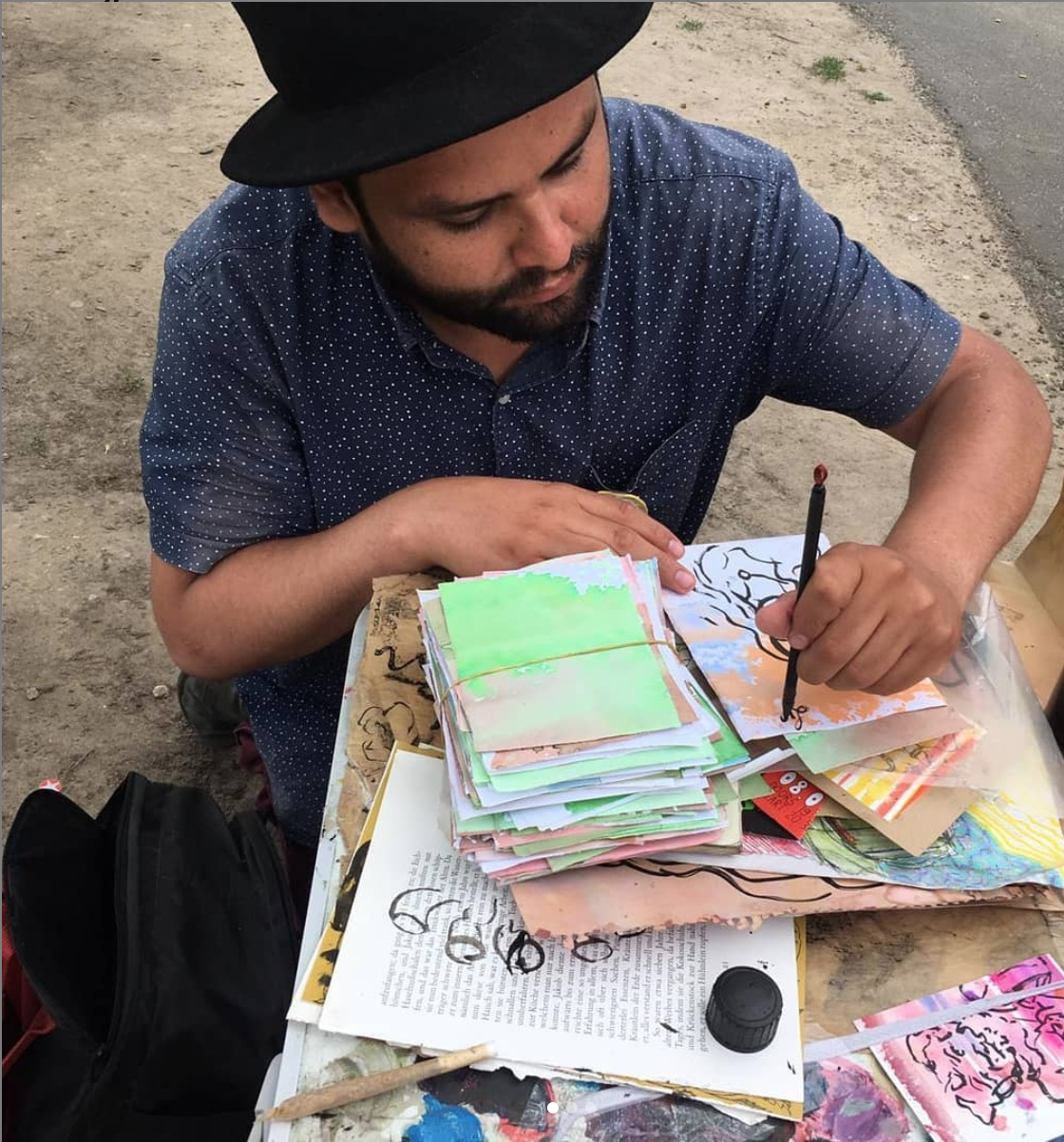

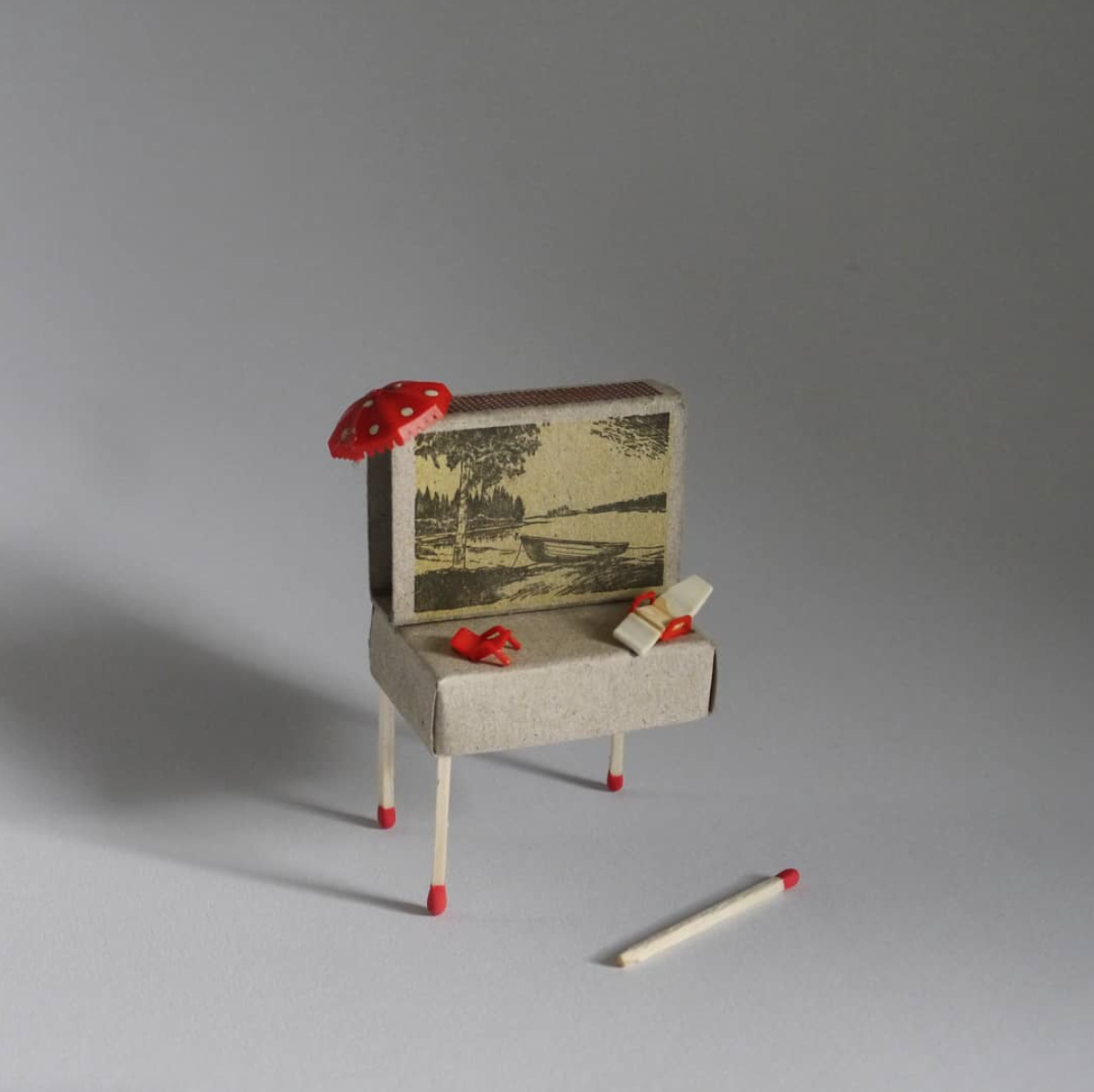

Lucas Rueckner at his first solo exhibition “Último Juguete” (The Last Toy) at ICPNA in Lima-Peru, 2016

Do not let yourself be deceived by the German surname that the Peruvian artist carries. It was inherited from his non-biological father. More significant to his name are his childhood memories, to which he remains strongly bound. He was born and raised in the northern Talara prefecture, not too far from the beach and sounds of crashing waves. Carrying his love for noise into his adulthood, he is also a singer and trumpeter. Yet a much more significant memory is his uninhibited playfulness and sunny curiosity that plays not just into the creative process, but also his self-expression.

To date, his art has embraced the theme of childhood creativity. If we take his first solo exhibition (“The Last Toy”) at the ICPNA Gallery in Lima-Peru as an example, it becomes clear that Lucas Rueckner understood the nature of creative freedom early on. We typically hold artistic creativity to the standards set by the commercialised contemporary art world, only to forget that the innocence and disregard of any such parameters had enabled the “most creative phase in our lives.” His interactive installations thus invite onlookers to play with the three-dimensional materiality of his works, in order for them to identify the limitations to their own imagination.

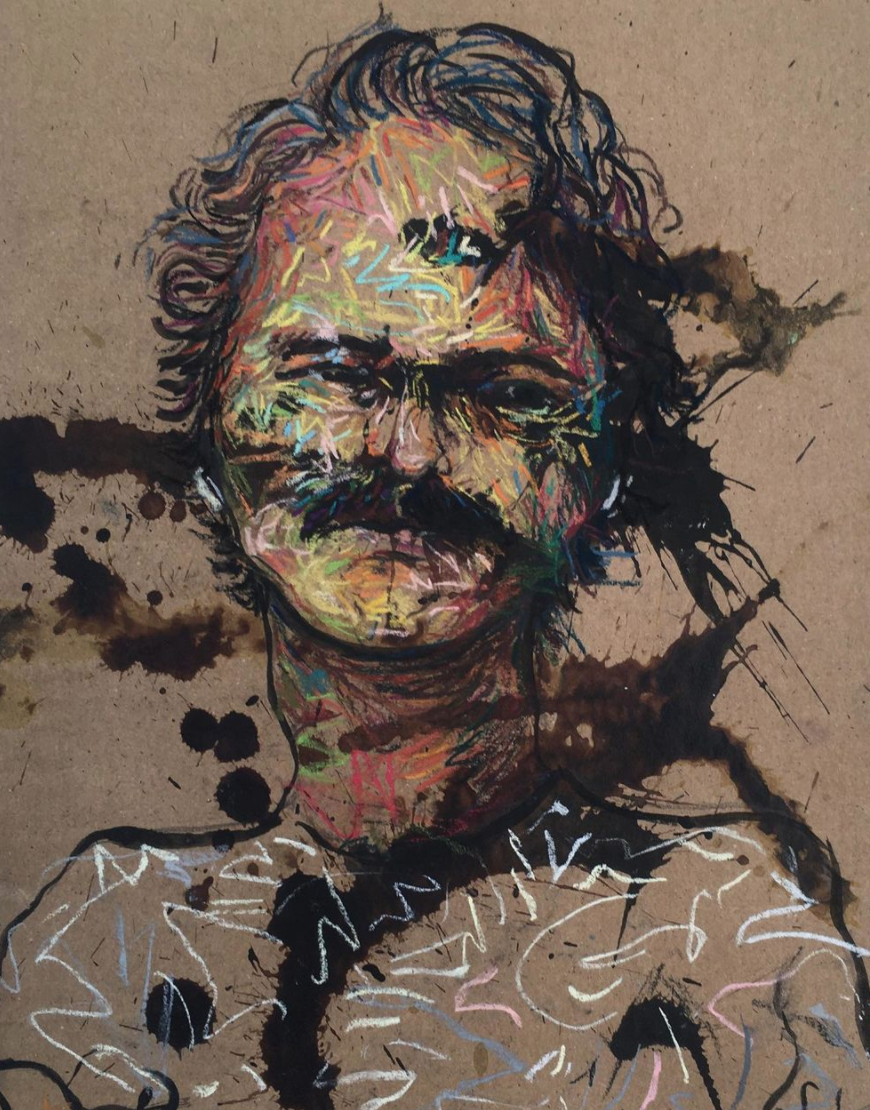

His studio-home in Berlin left me with the impression that the artist remains with little creative bounds. He sat in front of me in late 2020, with his signature fried-egg brooch pinned to his jacket. While he maintains an earnest facial expression, his empathetic chopped-up laughter reveals a quirky humour that materialises in his artistic productions. The sculptural characters that he has made from found objects resort in his living space, whilst the colourful scribbles and swirls of his most recent abstracts works fill the walls. Particularly splashy are the glittery self-made brooches clamped together by a hot glue gun. One features a miniature plastic dinosaur with pink shoes, while another, two fish kissing upside down.

Lucas Rueckner takes a non-traditional approach to art. It is not in his nature to set intentions for his creative projects. He rather treads in the unknown depths of his consciousness until emotional impulses surface that motivate him to create:

“I see myself as a kid who likes to play with his paintings and brushes […] My art is between creativity and play, or the playground.”

To his dismay, the Peruvian art sector could not afford the structural freedom that he craves. When Rueckner graduated with a Fine Arts degree from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, he did not feel like packaging his creativity into an artistic name. How was there any space for it if his artistic “achievement” depended on public recognition? Neither could he visualise a living based on his open-ended creative spurs. He is aware that his works typically ‘appear’ unfinished. At least, so he was repeatedly told by his university professors.

Thus motivated by his artistic integrity, Rueckner pursued the unknown abroad. He traveled various cities in Spain, Italy, France, Holland and eventually Germany until he encountered the experimental character that marks Berlin’s creative city:

“I was impressed by the freedom that artists had to showcase their work in the streets and in whatever format they wanted […] I took the decision to move to Berlin, because I found reinvention and constant change.”

Berlin Photograph by BLOC Art Peru

The German capital is well-known to attract the young, hip and creative industrious into its underground belly. Characterised by counter-cultural practices, the scene lacks any sort of highbrow sophistication. Frankly, Berlin was famously branded as “poor, but sexy” by 2003-mayor Klaus Wowereit. He was referring to the curious metropolis that emerged with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the high unemployment rates and low living costs alike that have sustained its distinctive cultural vibrancy.

When the German Democratic Republic (DDR) collapsed, it left not only a broken state, but also an ideological vacuum and sprawl of abandoned spaces. These were transformed into an experimental laboratory of socio-utopian galleries, ateliers, studios, bars and party cultures. To this day, its protagonists absorb the memories of hardship and ability to reinvent itself. They define the city by its social spaces that vegetate often decrepit concrete buildings with cultural opportunity.

One such example is the ‘Greenhouse,’ a striking green office building located in the middle of no-man’s land in Berlin’s Tempelhof district. The four top-most levels were rented out as project spaces and ateliers, which soon escalated into a squat for artists and musicians. Lucas Rueckner was introduced to it by his (german) girlfriend at the time, as he sought new accommodation and connection to other creatives. Rising up between a metal scrap garden and a freeway exit, the “creative factory” stood anonymously yet proudly:

“It was dirty and there was graffiti everywhere. Drugs too. A very intense and kind of out-of-control atmosphere. I was there when the period of this place was ending. There were a lot of scandals and problems with the administration.

[…] but in my floor, I met a Polish guy who was playing experimental music with machines. This noise…it was a contemporary vision of art, not traditional or conservatory. I absorbed the sounds and new expressions like a sponge.”

Lucas Rueckner

Like Rueckner, others will continue to speak of the Greenhouse with great admiration. They experienced cultural democracy after all! Not only did the space equip them with the facilities and opportunities to interact openly, it has also given them a taste for cultural co-creation. They have seen heterogeneous blends of (sub-)cultures melt into a neutral community that encourages and celebrates individual self-expression. They have felt a refinement of their senses, their boundaries pushed and their vehemence speaking directly to them. And they have understood that they must share their cultural awareness and competencies in order to strengthen their own.

Project spaces as such may easily get out of hand, while Berlin’s infamous club cultures are known to come and go. Attempting to preserve them would run directly against their transgressive ethos. Hence, its participants know that with every fold in time, they engage with- and shape the shared heritage of the moment. In fact, urban researchers have described Berlin as:

"a city condemned forever to becoming and never being; […] that the city is in a constant process of transformation.”

It is then worth asking: if the collective underground heritage emerges with every moment, are its protagonists - is Lucas - always adrift in a pipe dream?

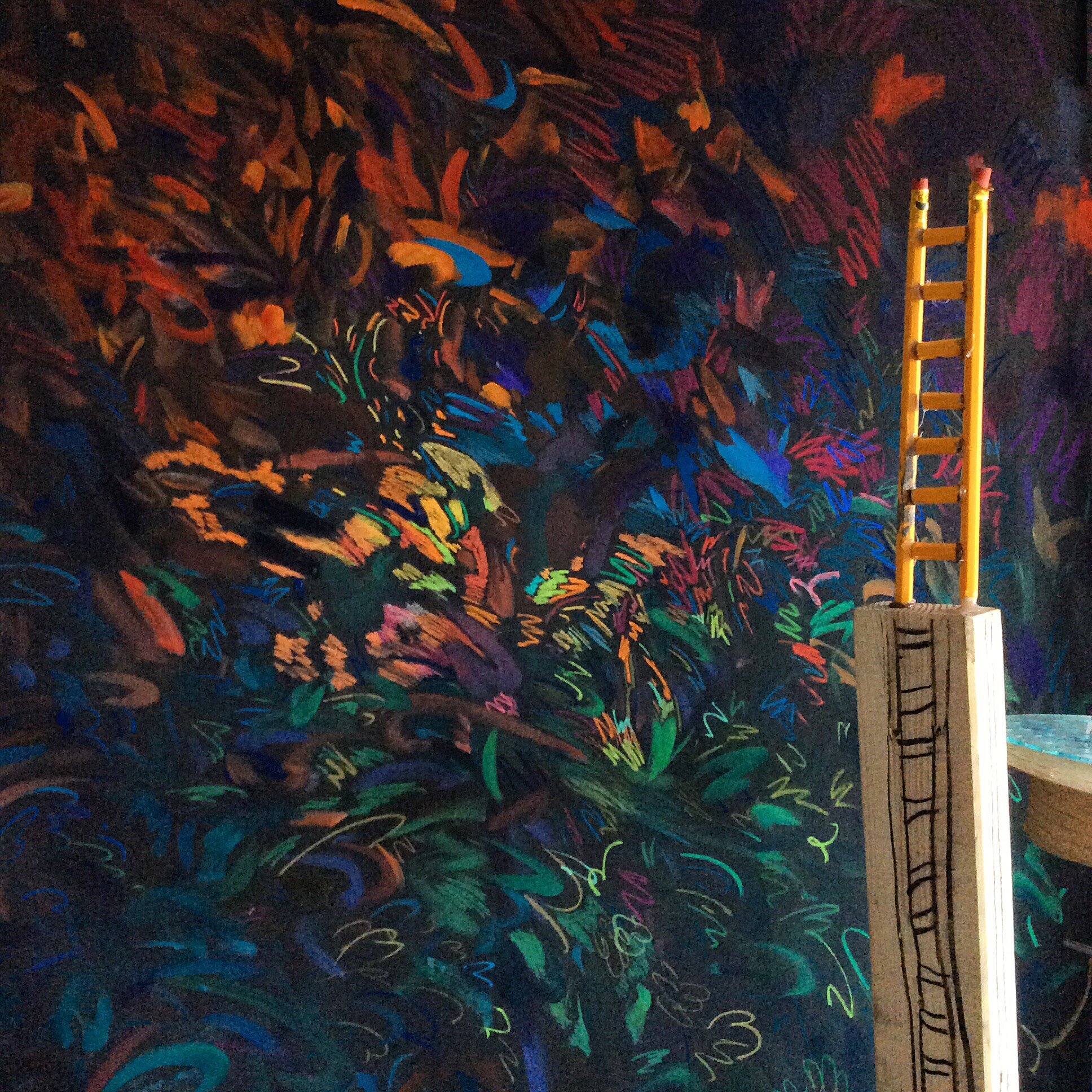

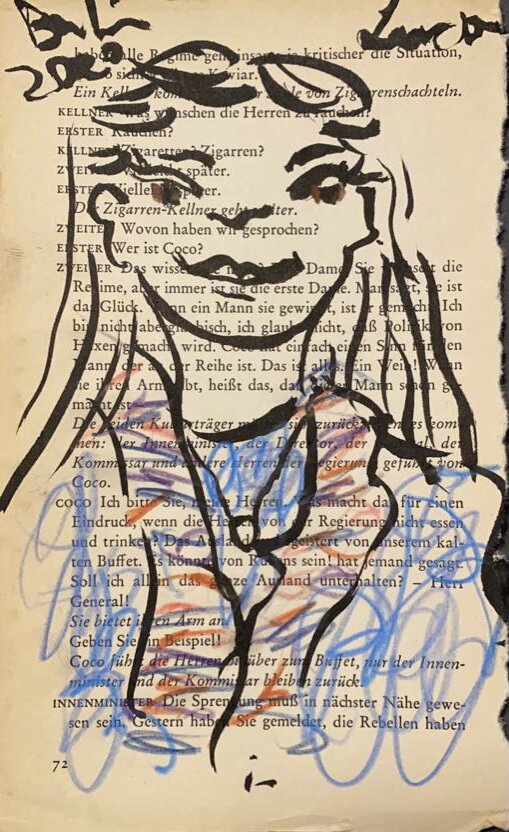

‘Untitled’ by Lucas Rueckner

Some might argue that the artist’s challenge is to venture into the ‘eye of the storm,’ a headspace in which the endless distractions and impulses fade into a silence that supports artistic direction and action. But is it not precisely the storm, the spontaneous spirit of the creative class, that provides unique perspective and inspiration?

Others would highlight cultural harbours, such as the Greenhouse, as essential to the survival of- and survival in- Berlin’s creative city. After all, it is the music, dialogue, dance and being-in-relation that upholds the creative infrastructure and promises the city economic growth.

Lucas Rueckner, on the other hand, has struggled towards a sustainable foundation from which he can withstand and benefit from the storm. The secret pacemaker has been his community and faith in the passing of time. He believes, and therefore manifests, that his creative impulses and artistic development emerge organically.

A spool of film is playing in his mind. Lucas Rueckner remembers the endearing social interactions, streets and neighbourhood communities clearly. When he had first arrived in Berlin, he marvelled at the kaleidoscope of faces, their features and gestures. The artist had to try his hand at a new approach that would bring him close to the local diversity! Setting up his stand at the traditional Sunday markets (i.e. Mauerpark, Maybachufer), he began to offer ‘Ugly Portraits’ to passerby. The colourful drawings that succeed after a short minute outline the characteristic expressions of the people. He has developed a regular practice that unites his abstract and figurative tendencies in a singular format. “It is an approach that Berlin gave me,” he tells me in an adamant tone as though to express his gratitude to the city.

Rueckner has nothing short of a sustainable foundation from which he can withstand and benefit from the silence that has replaced the storm. He is one of many who benefits from the 3-billion-aid package that the German Federal Government has offered the arts sector. Whilst watching the snow settle on nearby rooftops and waiting for yet another Covid streak to pass over, he resides in an art residency that is docked to the city’s edge. Its name ‘Backsteinboot’ (Brick Boat) is emblematic of the industrial brick building that sits afloat on a small island in the Spandau district river. As a ‘center of professionalisation,’ it promises its 14 residents the “tools, facilities, feedback and opportunities to invest into creativity and the development of new concepts.” Some artists focus on sound and video production, while others paint or perform. The collective project space offers itself as a makeshift stage for experimentation and cultural production.

The space is strikingly vacant in comparison to earlier days. Although the experimental spirit remains amongst the creative collective, the Peruvian artist is feeling constrained. The waning slowdown of the underground culture has pushed the artist to question his intentions and doings:

“I have felt morally obliged to connect to my work as it is…the last thing that I have? […] I don’t feel stuck in the moment, but…something is changing within me. I am in an introspective mood and am finding many projects within myself that I want to touch and keep, before I get distracted.”

To his astonishment, the works that occupy his walls and his space now mark the end to a chapter. They were exhibited just days before the global pandemic swept across Europe. Now, Lucas Rueckner journeys inwards. By unpacking his very own artistic ego and studying the origins of his impulses, he hopes to reside deeper in each present moment.

His interest in childhood creativity remains as he begins his Master in Art Therapy, an interest that he had long wanted to explore:

“I find it interesting how we have created traumas since the beginning of our childhood. Our psychology and perception of the world changes every day, […] but we do not realise how blind we are in the present. There is another dimension and touchable experience that I want to perceive and involve other people in, to help solve their traumas.”

Lucas Rueckner has made a contract with himself; one that he no longer signs as a “kid who likes to play with his paintings and brushes,” but as a “warrior who survives with his tools and colours.” He admits that his self-visualisation may be idealistic or fantastical, but believes that his manifestation may transform just an idea into something more concrete. His faith remains in passing of time.

‘Untitled’ by Lucas Rueckner

External Source:

Schofield, J. and Rellensman, L., 2015. Underground Heritage: Berlin Techno and the Changing City. Heritage and Society. 8(2). pp. 111-138.